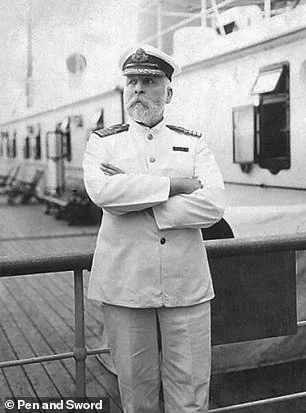

When Captain Edward Smith went down with the Titanic on that frigid morning of April 15, 1912, it seemed to confirm what many had already started to whisper: that the 'unsinkable' ocean liner was, indeed, cursed.

In the months and years that followed, reports swirled about a possible jinx. Were early mishaps a precursor to eventual disaster? Was the ship hexed by an Egyptian mummy's coffin lid stored in its hold?

Psychics had warned passengers not to sail on the ship's maiden voyage across the Atlantic.

And many of those fortunate enough to survive the sinking - which claimed more than 1,500 lives - died later of mysterious illnesses.

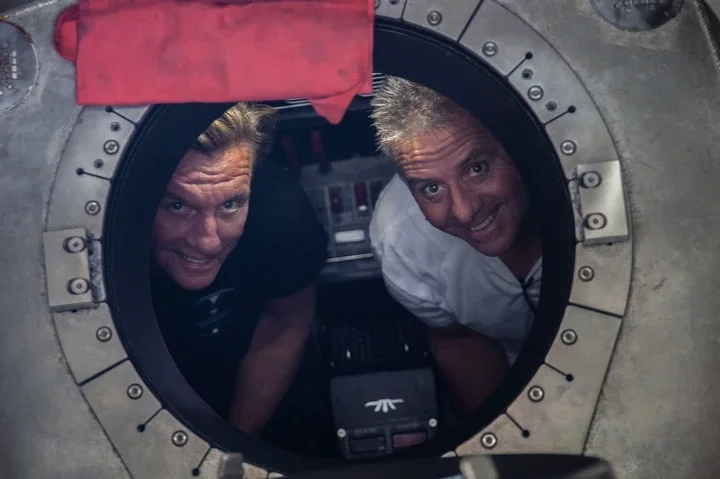

Even more than a century later, in June 2023, the Titanic curse was said to have struck again with the catastrophic implosion of the OceanGate Titan submersible, a private expedition to view the wreck that claimed the lives of all five on board.

Now a book - containing previously unpublished private letters and family photographs - reveals the true extent of the so-called curse on Edward Smith's family that haunted them long after his death.

Helen 'Mel' Melville Smith, the captain's only child, was 14 when he died and the family was thrust into the spotlight.

Initially, her father had been blamed for the sinking but she could not escape the dubious fame the doomed ship brought her even after his name was cleared.

Hers was a life surrounded by wealth, art and Russian spies, writes Dan Parkes in Titanic Legacy.

Yet, by the time Mel was 49, she had not only lost her father but also her mother, husband, son, and daughter - each in unusual circumstances.

Less than 10 years after she quietly married the dashing Sidney Russell Cooke on July 3, 1930, a maid discovered his body lying in a pool of blood in the couple's upmarket home at 12 King's Bench Walk, London. He had been shot through the stomach with a double-barreled hunting rifle.

A stockbroker, author and would-be politician, Cooke had been living a secret double life - as an MI5 spy, sometimes described as a 'prototype James Bond', and as the erstwhile gay lover of economist John Maynard Keynes.

Friends at the time described his death as an 'inexplicable mystery... he had no personal financial worries. His domestic affairs were of the happiest'.

And a coroner's inquest the day after the shooting ruled that Cooke's tragic death had been the result of an accident while cleaning the gun.

But suspicions still swirled. Could it have been suicide?

'In his 1997 film,' writes Parkes of the Titanic blockbuster starring Kate Winslet as survivor Rose DeWitt Bukater, '[the director] James Cameron included a reference to fictional villain Caledon Hockley shooting himself after financial ruin during the stock market crash.'

In the closing sequence, using a framing device set in the present day, the actress Gloria Stuart gives voice to an elderly Rose, recounting the story of the man she almost married: 'The Crash of '29 hit his interests hard, and he put a pistol in his mouth that year. Or so I read.'

Some commentators have drawn a connection between that line of dialogue and the mysterious death of Sidney Russell Cooke, says Parkes.

It was also revealed that Cook had been to lunch with his former lover, Keynes, the day before his death while Mel was recuperating from surgery at a nursing home.

Had he shot himself 'in a lonely paroxysm of miserable regrets at married life?' mused the historian Richard Davenport-Hines in his biography of Keynes.

Or had it been murder?

'A cause that was never raised during the inquest,' continues Parkes, 'except perhaps in hushed and unrecorded conversations, was that something far more sinister had occurred.

'It was not revealed in the press or coroners' reports - for rather obvious reasons - that Sidney worked for MI5 and the apartment in which he was found dead had been used as a "safe house", along with reports of spies sending messages to 12 King's Bench Walk requesting a "revolver for self-defense".'

As a result, some believed he had been killed by the Russians.

Cooke's funeral was rapidly arranged and, as the gossip died down, Mel found herself a wealthy woman.

In his will, he left £120,098 - the modern equivalent of about $6.6million. However, he stipulated that if Mel re-married the estate would pass to their twins, who were seven years old at the time.

For all her riches, her husband's death was just the beginning of a series of tragedies.

Less than a year later, her mother, Eleanor, the Titanic captain's partially blind widow, was struck by a taxicab outside her home, a few months shy of her 70th birthday.

She had been holding an umbrella in the rain, which may have further obscured her already poor vision.

Heartbroken, Mel escaped London and its memories, relocating to the Isle of Wight, a small island off the south coast of England. But fate followed.

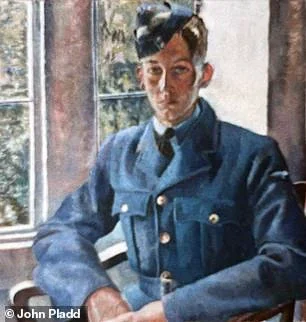

Her son Simon, a talented fighter pilot, was sent to attack an enemy shipping convoy off the coast of Norway in March 1944 when his plane was shot down.

The mission was successful but Simon, aged 20, did not survive the crash. His body was never recovered.

Three years later, in 1947, her daughter Priscilla succumbed to polio a year after getting married.

'There is no record of how Mel responded to the loss of both her children,' writes Parkes, 'other than a moment when she confided to one of her few intimate friends that she was afraid of forming close relationships because they seemed destined to end in tragedy.'

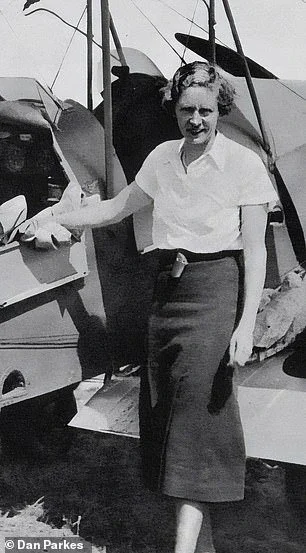

But, despite being plagued by heartache, Mel remained resilient, living life more fully than most women of the day - even gaining a pilot's license in 1934.

'Most likely Mel was inspired by a crop of aviatrix pioneers of the 1930s,' writes Parkes, 'such as the young Yorkshire woman Amy Johnson who flew solo from England to Australia in May 1930 in a Gipsy Moth, taking 19 days. She was only 27.

'This was followed by New Zealander Jean Batten who also flew a Gipsy Moth from England to Australia single-handedly in 1934, taking just 15 days. She was just 25 and was known for her aviation achievements and her glamorous appearance.

'Pushing the limits of record-breaking technology is inherently risky. As with the infamous disappearance of Amelia Earhart in 1939, Amy Johnson likewise vanished without a trace when her plane crashed into the Thames Estuary in 1941.'

And, while Mel felt unable to marry again because of the caveat in the will, she had her fill of romance, taking a string of lovers, including her flying instructor, 32-year-old Flight Lieutenant Christopher Clarkson.

'Clarkson was three years younger than Mel,' notes Parkes. 'And one of her more well-known love interests was even younger - 18 years younger.'

Mel met the celebrated portraitist David Rolt when he was in his early 20s, and their relationship, which survived both his marriage and divorce, lasted until her death. He painted her and the twins several times.

She died in 1973, aged 75. With her, Captain Smith's family line ended - but not, if some can be believed, the curse that had clung to it for more than six decades.

Titanic Legacy: The Captain, his Daughter and the Spy by Dan Parkes is published by Amberley Publishing

Comments